Somewhere along the way, we were taught to believe in redemption as a kind of promise.

The idea goes something like this: if you work hard enough, feel deeply enough, prove yourself thoroughly enough – then things will finally come back into place. The arc will complete itself. It will all resolve. You’ll be changed. “Welcom back!” you’ll hear. And whatever you went through will finally make sense.

But that promise, for many of us, has come with quiet conditions.

Conditions that often go unnamed, though we feel them just the same. They whisper that healing should make you more acceptable. That your pain, once properly processed, shouldn’t leave much of a mark. That transformation, if it’s real, will be obvious – tidy, contained, and comforting to those around you.

And so, without even realizing it, we start to shape our inner world to match that outer expectation.

That kind of pressure doesn’t always feel like pressure. It can arrive gently. Maybe as a hope that your story will inspire someone. Or as a subtle pull to turn what caused pain into something teachable. And, to this, sometimes it shows up in the language we hear so often:

“Everything’s a lesson,”

“Your pain is your purpose,”

or

“This happened for a reason.”

These words are often offered with care. But over time, they can start to shift how we relate to our own pain. The wound is no longer just a place we visit with tenderness – it becomes something we’re expected to shape, manage, and ultimately showcase.

What began as a hope for belonging and relation quietly gets pulled into performance.

And what still aches and bleeds is now asked to be beautiful.

As such, also, sometimes what gets called redemption is actually just a performance of accountability.

But the two aren’t the same.

Accountability happens in relationship – it’s slow, lived, often quiet.

It stays close to the harm and the repair.

Redemption, by contrast, is usually about being seen in a certain light. It’s tied to being forgiven, approved of, or declared changed.

One is about presence. The other is about resolution. When we confuse the two, we risk treating relational repair as something that can be achieved through optics alone.

In the midst of all that, something personal starts turning into something else. Not because we’re trying to deceive anyone – but because we long for return.

We want to be welcomed back. We want the rupture to matter, to lead somewhere. And often without meaning to, we begin to carry an invisible measuring stick. We start to ask: Was it worth it? Did it change me enough?

That’s not just personal longing. It’s cultural conditioning.

We live inside systems that reward resolution and fear what doesn’t close. Systems built on control, productivity, and appearances.

And when healing passes through that filter, it can become another form of compliance.

Even the most intimate forms of suffering get swept up into questions of value, of commodification – held up against what can be made useful, presentable, even marketable. The wound is no longer just a wound. It becomes something to sell, or to prove.

So when we talk about “redemption arcs” – those neat, uplifting narratives we see in stories and sermons alike – it’s important to name that they didn’t come from nowhere. They were shaped by the very systems they now pretend to transcend. They reflect a longing for clarity, yes, but also a deep discomfort with what remains unresolved.

They comfort the onlooker. They reassure us that pain is temporary, that it leads somewhere good, and that if someone else got through it, we probably can too.

But the path towards Self doesn’t lead that way.

It doesn’t move in clean arcs. It returns. It contradicts. It slips into the body and hides, then re-emerges without warning. Sometimes it resists being turned into a story at all. It doesn’t offer closure. It doesn’t always make sense. And it doesn’t owe anyone a transformation.

That doesn’t mean becoming isn’t real. Of course we change. But maybe we don’t change in the way we’ve been taught to expect.

Maybe some parts of us never resolve – and maybe that’s not a failure. Maybe some processes stay sacred because they can’t be changed and they can’t be packaged.

Maybe staying near what’s unfinished is part of what keeps us human.

So what happens when we step outside the redemption arc entirely? When we stop asking our wounds to prove something? When we stop narrating pain as if its job is to deliver a breakthrough?

What might emerge if we let the wound speak – not as performance, not as confession, but simply as presence?

This isn’t about glorifying suffering. It’s about recognizing how easily even healing and The Work gets shaped by the need to be palatable.

Many of us have been taught – explicitly or not – that to be loved, we must be tidy. Understandable. Safe.

So we contort.

We shape pain into something that won’t scare anyone. We rehearse our truth until it sounds like insight. And if it doesn’t land well, we try again – crafting new masks that we can still call “authentic,” so long as they’re approved.

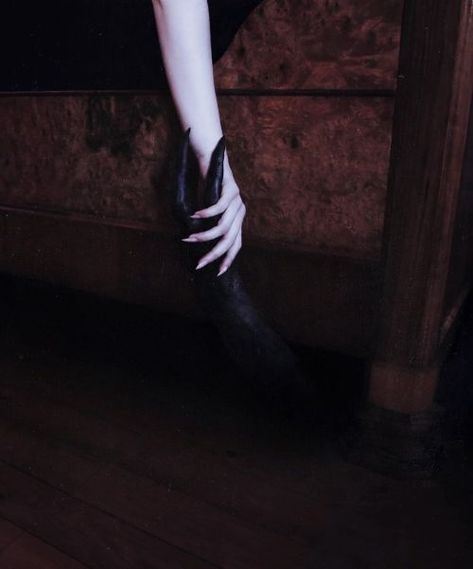

What we’re often running from is the fear of being seen as the monster – the one who’s too angry, too contradictory, too much.

But the parts of us we try to exile still wait for relationship.

The monster doesn’t want fixing. It wants presence. It wants to be known without needing to be neutralized.

And yet, this is where we flinch – because most of us don’t know how to love what we can’t explain, or who we deeply disagree with, or what doesn’t reassure us.

Maybe what’s needed isn’t transformation in the way we’ve been taught to imagine it – not as a tidy before-and-after, but as an ongoing relationship with what’s still unresolved. Something that doesn’t ask to be fixed. Something that asks to be met and held without condition.

This is where the idea of redemption begins to unravel. Because if redemption still depends on a person becoming easier to understand – or easier to love – then it’s not redemption. It’s assimilation.

What we need is not a story that saves us.

What we need is a practice that keeps us in relationship with what has not been solved.

And that includes each other.

Maybe it was never about redemption.

Maybe it was always about staying close to what we were taught to fear – what we were told to abandon – in ourselves, and in each other.

Leave a comment