My brother and I often swap books that we’ve read & that’s how I recently came in possession of a book by Aleksander Hemon, my first by this author. This was not a book on grief, but the other night as I opened the book to start reading I noticed that he dedicated the book to his wife & daughters, with an (RIP) after one of their names. Suddenly I felt an affinity to the author & Googled his name to find out more about him & his loss. That’s how I came across his article in the New Yorker about his daughters illness & subsequent death, titled, The Aquarium. There’s something about sharing the same loss, no matter how it occurred, that makes you feel understood. In this case, a writer, which made me want to find & read everything he wrote on grief, knowing I would find words expressing the loss & pain in ways I can’t.

There’s this romanticization of grief in modern society, maybe from movies or books, that makes it seem so noble. We epitomize people who grieve “gracefully” or have some epiphany in their grief & find some great meaning for their lives. As Hemon says in his article, “One of the most despicable religious fallacies is that suffering is ennobling—that it is a step on the path to some kind of enlightenment or salvation.” The truth is, death is just a part of life, & hundreds of thousands of people die each day. Regardless of our religion or beliefs, suffering and death does nothing for those who died, or us, or the world.

Hemon’s daughter’s illness, he says, made him feel as if he were living behind glass: visible yet separate from the rest of the ordinary world. It is beautifully written. It’s also harrowing and brutally honest, brimming with the rawness of his pain. Many readers have taken it hard. One confesses the piece left her physically ill. Another questions why Hemon wrote it at all. “Why would anyone want to read a story like this?” she asks. “What possible benefit is there in it?” Is there any meaning in a child’s death? Hemon doesn’t seem to think so. After his daughter died, he says, he and his wife left the hospital like “refugees,” driving on “meaningless” streets. “[Her] suffering and death did nothing for her, or us, or the world,” he writes. “We learned no lessons worth learning; we acquired no experience that could benefit anyone.”

“The death of a child changes everything in ways that are too many, too small and too big to recount.”, Hemon continues. One of the things parents fear most when they lose a child is that he or she will be forgotten. We feel that urgency in Hemon’s memoir, written furiously in the months after his daughter’s death. Like Coleridge’s ancient mariner, he has borne witness to an extraordinary event and now is condemned to tell the tale. But through his memoir, Hemon does more than just recount the story of his daughter’s brief — and clearly meaningful — life. He memorializes it. In another of his books “The Book of My Lives”, though his writing deals with not one, but two unthinkable human tragedies, war and the loss of a child, it maintains a sense of humor and livelihood. It’s so aptly titled – it is a book of life, on life, with life. While at times it leaves you teary-eyed, it never leaves you without hope. It’s not devastating but instead empowering to follow the author trudge through the hand he was dealt one step at a time.

“There’s a psychological mechanism, I’ve come to believe, that prevents most of us from imagining the moment of our own death. For if it were possible to imagine fully that instant of passing from consciousness to nonexistence, with all the attendant fear and humiliation of absolute helplessness, it would be very hard to live. It would be unbearably obvious that death is inscribed in everything that constitutes life, that any moment of your existence may be only a breath away from being the last. We would be continuously devastated by the magnitude of that inescapable fact. Still, as we mature into our mortality, we begin to gingerly dip our horror-tingling toes into the void, hoping that our mind will somehow ease itself into dying, that God or some other soothing opiate will remain available as we venture into the darkness of non-being.

But how can you possibly ease yourself into the death of your child? For one thing, it is supposed to happen well after your own dissolution into nothingness. Your children are supposed to outlive you by several decades, during the course of which they live their lives, happily devoid of the burden of your presence, and eventually complete the same mortal trajectory as their parents: oblivion, denial, fear, the end. They’re supposed to handle their own mortality, and no help in that regard (other than forcing them to confront death by dying) can come from you—death ain’t a science project. And, even if you could imagine your child’s death, why would you?

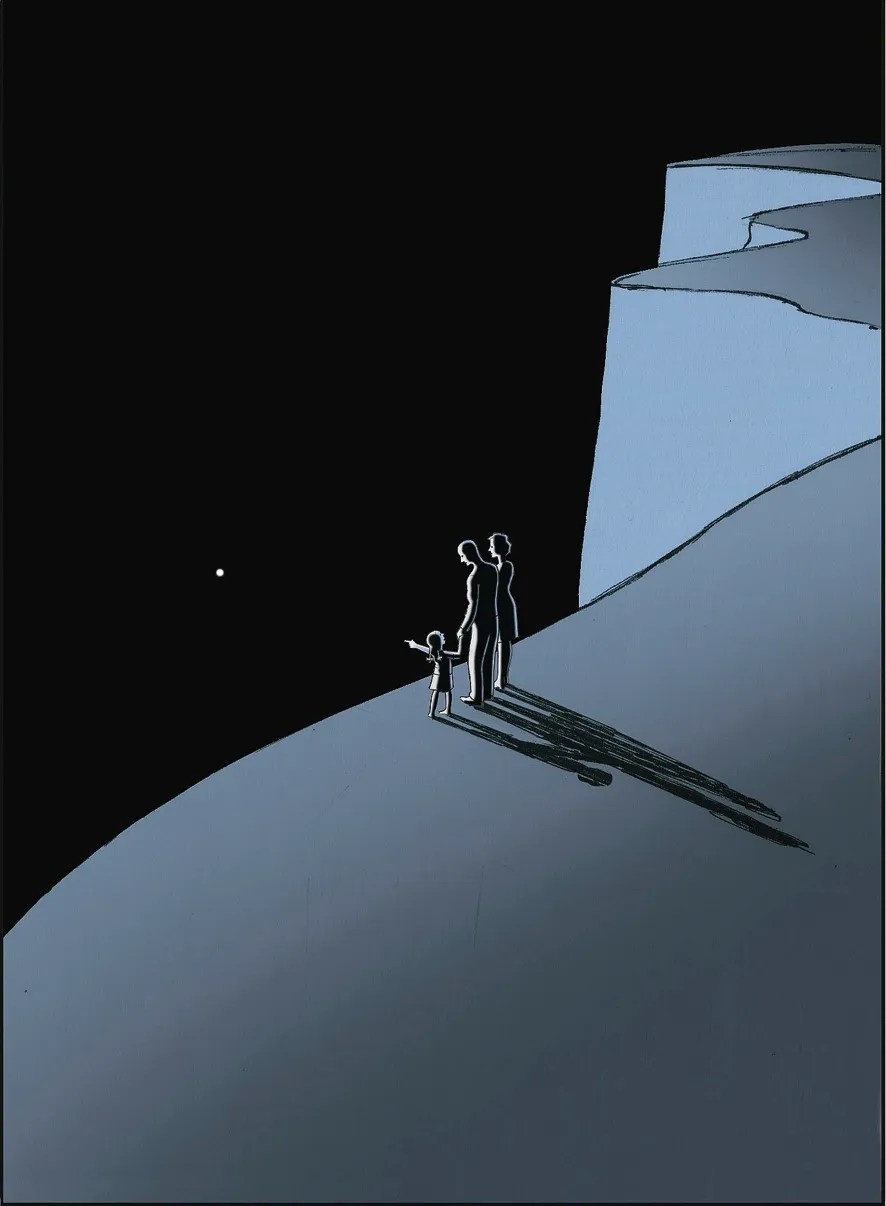

One early morning, driving to the hospital, I saw a number of able-bodied, energetic runners progressing along Fullerton Avenue toward the sunny lakefront, and I had a strong physical sensation of being in an aquarium: I could see out, the people outside could see me (if they chose to pay attention), but we were living and breathing in entirely different environments. [My daughter’s] illness and our experience of it had little connection to, and even less impact on, their lives. [My wife] and I were gathering heartbreaking knowledge that had no application whatsoever in the outside world and was of no interest to anyone but us: the runners ran dully along into their betterment; people reveled in the banality of habit; the torturer’s horse kept scratching its innocent behind on a tree.

[My daughter’s illness] made everything in our lives intensely weighted and real. Everything outside was not so much unreal as devoid of comprehensible substance. When people who didn’t know about [her] illness asked me what was new, and I told them, I’d witness them rapidly receding to the distant horizons of their own lives, where entirely different things mattered. After I told my tax accountant that Isabel was gravely ill, he said, “But you look good, and that’s the most important thing!” The world sailing calmly on depended on platitudes and clichés that had no logical or conceptual connection to our experience.

I had a hard time talking to well-wishers and an even harder time listening to them. They were kind and supportive, and [my wife] and I endured their expressions of sympathy without begrudging them, as they simply didn’t know what else to say. They protected themselves from what we were going through by limiting themselves to the manageable domain of vacuous, hackneyed language. But we were far more comfortable with the people who were wise enough not to venture into verbal support, and our closest friends knew that. We much preferred talking to [the doctors] who could help us to understand things that mattered, to being told to “hang in there.” (To which I would respond, “There is no other place to hang.”) And we stayed away from anyone who we feared might offer us the solace of that supreme platitude: God. The hospital chaplain was prohibited from coming anywhere near us.

One of the most common platitudes we heard was that “words failed.” But words were not failing [my wife] and me at all. It was not true that there was no way to describe our experience. [We] had plenty of language with which to talk to each other about the horror of what was happening, and talk we did. The words of [the doctors], always painfully pertinent, were not failing, either. If there was a communication problem, it was that there were too many words, and they were far too heavy and too specific to be inflicted on others. We instinctively protected our friends from the knowledge we possessed; we let them think that words had failed, because we knew that they didn’t want to learn the vocabulary we used daily. We were sure that they didn’t want to know what we knew; we didn’t want to know it, either.

Though I recall that moment (daughter’s death] with absolute, crushing clarity, it is still unimaginable to me. And how do you step out of a moment like that? How do you leave your dead child behind and return to the vacant routines of whatever you might call your life? One of the most despicable religious fallacies is that suffering is ennobling—that it is a step on the path to some kind of enlightenment or salvation. [My daughter’s] suffering and death did nothing for her, or us, or the world. We learned no lessons worth learning; we acquired no experience that could benefit anyone. And [she] most certainly did not earn ascension to a better place, as there was no place better for her than at home with her family. Without [her], [my wife] and I were left with oceans of love we could no longer dispense; we found ourselves with an excess of time that we used to devote to her; we had to live in a void that could be filled only by [her]. Her indelible absence is now an organ in our bodies, whose sole function is a continuous secretion of sorrow.”

~Aleksandar Hemon, Aquarium

Leave a comment