I first learned the term “Grief Brain” while driving to Maine from Arizona accompanying one of my best friends as she closed down a rental home she and her husband had there. Her husband had just died & she was left dealing with all that entailed, including bringing furniture back by a certain date, requiring that we drive completely across the US in a short amount of time. Being with her in close quarters for over 40 hours I got to know how grief was affecting her & one of the first things I noticed was how scatter-brained, forgetful & clumsy she had become. This friend was always a power businesswoman, always at the top of her game. She had her own business & was quite successful. So seeing her “lose her mind” was concerning. I’ll admit there were times I wondered if she was completely insane.

I had never really closely dealt with someone in the early stages of profound grief (this was prior to my son’s passing) so it was all new to me. And it was a bit scary seeing my friend lose her basic brain functions & common sense. So I Googled “effects of grief” and one of the terms that came up frequently in articles on the topic is “Grief Brain”.

“Grief impacts us emotionally and physically. The intensity of this loss can lead to a symptom known as Grief Brain. When this happens, you may find yourself having trouble sleeping, concentrating, and remembering simple things. Grief can rewire our brain in a way that worsens memory, cognition, and concentration. You might feel spacey, forgetful, or unable to make “good” decisions. It might also be difficult to speak or express yourself.”

~PsychCentral.com

Shortly after my son died I started experiencing that brain fog myself, forgetting things, getting lost, etc. Some things were trivial & weren’t a big deal, but there were also times I forgot important work deadlines, appointments, food on the stove, etc. Once, I forgot to bring in our little geriatric dog from the yard & he fell in the pool. (Thankfully I got him in time.) For someone like me, who is normally high functioning & pride myself in an excellent memory, this was debilitating, frustrating and humiliating.

Fear of the unknown is the worst, so I started reading more about it. I found an excellent book by a neurologist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. In her book, Lisa Shulman, whose husband (also a neurologist) died of an aggressive cancer, describes feeling like she was waking up in an unfamiliar world where all the rules were scrambled. On several occasions in the months after her husband’s death, she lost track of time. Once, after running an errand, she drove to an unfamiliar place and ended up unsure of where she was or how she got there. She pulled off the highway and had to use her GPS to navigate back home.

“The problem isn’t sorrow; it’s a fog of confusion, disorientation and delusions of magical thinking. The emotional trauma of loss results in serious changes in brain function that endure. Grieving is a protective process. It’s an evolutionary adaptation to help us survive in the face of emotional trauma. Neuroplasticity moves in both directions, changing in response to traumatic loss, and then changing again in response to restorative experience,”

~Lisa Shulman, Before & After Loss

Scientists are increasingly viewing the experience of traumatic loss as a type of brain injury. The brain rewires itself — a process called neuroplasticity — in response to emotional trauma, which has profound effects on the brain, mind and body.

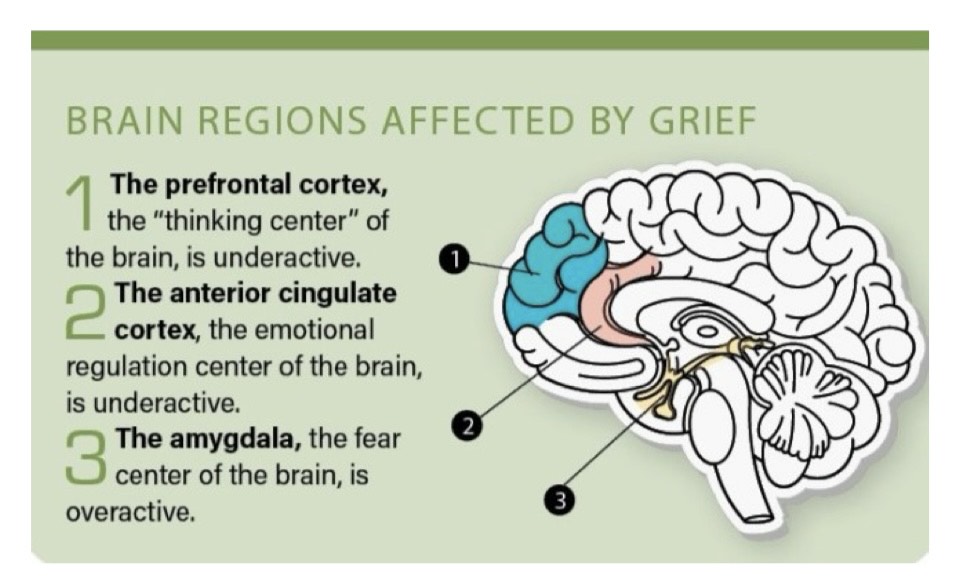

After a loss, the body releases hormones and chemicals reminiscent of a “fight, flight or freeze” response. Each day, reminders of the loss trigger this stress response and ultimately remodel the brain’s circuitry. The pathways you relied on for most of your life take some massive, but mostly temporary, detours and the brain shifts upside down, prioritizing the most primitive functions. The prefrontal cortex, the locus of decision-making and control, takes a backseat, and the limbic system, where our survival instincts operate, drives the car.

In an attempt to manage overwhelming thoughts and emotions while maintaining function, the brain acts as a super-filter to keep memories and emotions in a tolerable zone or obliterate them altogether. According to a 2019 study published in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, grievers minimize awareness of thoughts related to their loss. The result: heightened anxiety and an inability to think straight.

“I stopped at a gas station to fuel up before heading to the hospital to see my father [who was dying]. Standing at the pump, I thought about how he would never visit our new home. How we would never dance together again. I paid for my gas, got back in the car and drove out of the gas station — with the nozzle still lodged in my tank.

~Amy Patural, The Traumatic Loss of a Loved One Is Like Experiencing a Brain Injury

When I stopped the car, an onlooker who had watched the nozzle fly out of my car’s gas tank said smugly, “You’re lucky it snapped off.” I was embarrassed, ashamed and, most of all, in despair — not just because my dad was dying, but also because I was losing my mind. But I know now I was not alone: Frequently, humans who have experienced grief can recall incidents in which their brains seemed to stop functioning. I began to feel like I was the one recovering from a stroke. I fumbled to find words for common objects like lemon or cantaloupe. There were times when I blanked on my husband’s phone number and even my own.”

According to Helen Marlo, professor of clinical psychology at Notre Dame de Namur University in California, that’s not unusual. People who are grieving may lose their keys several times a day, forget who they’re calling mid-dial and struggle to remember good friends’ names.

“With grief, the mediator between the right and left hemispheres of the brain — the thinking and feeling parts — is impaired. The task is to integrate both, so you’re not drowning in the feelings without thought as a mediator or silencing feelings in favor of rational thinking. Each of us responds to grief differently, and that response is driven by the relational patterns that we lay down early in life, as well as the intensity of the grief. So even though regions of the brain might be firing and wiring the same way after loss, the way the mind reacts — the ‘feeling experience of grief — is unique to the individual.”

~Helen Marlo

Leave a comment